Author Archives: vlm

Rhythm Brings Order to Your Outdoor Space

How Landscape and Architecture Set the Tempo in Space

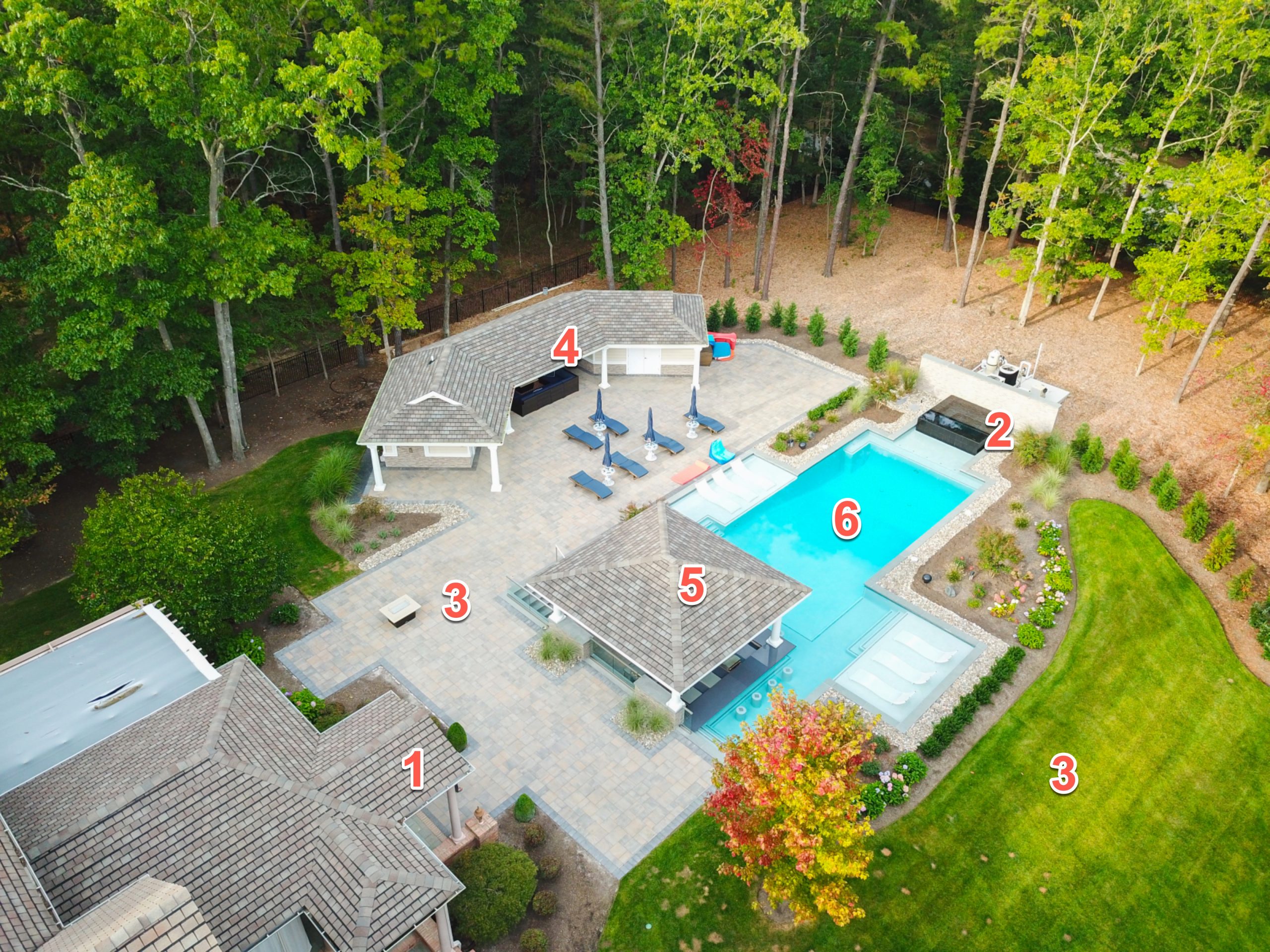

Classic modern pool design: You can feel the sophisticated rhythm in the balanced symphony of pool and patio shapes. Even the lounges join in the conversation of straight lines and right angles. The

umbrellas, set in a graceful arc, offer a counterpoint with their triangular, not-quite circular shapes.

Much as Emphasis sets the stage and brings focus to your WaterSpace, Rhythm—the fourth of Six Principles of Design—helps to coordinate all the pieces. Rhythm provides an underlying tempo that people sense. Without rhythm the world around is chaos.

Space as a place of comfort and order

When you plan a landscape, you use Rhythm to bring order to all the elements. Rhythm eliminates confusion. It helps guide us on our journey through a space. Its effect is physical and mental—like a green light, a stop sign, or crosswalk directing drivers and pedestrians.

We’ll discuss motion in greater detail in the next installment on Movement, the fifth Principle of Design. The two principles are so closely related they are often lumped together. For both rhythm and movement, the hardest part is applying familiar musical ideas in unfamiliar ways to landscapes and architecture:

• Sensing Rhythm beyond its sounds

• Seeing Movement in a medley of structural and natural elements that stand still

An Invitation to Dance

The rhythm you create in your space sets the tempo. The beat can be fast, slow, moderate, or change from one location to another within a designed space.

Like dance music, the rhythm of a space provides signals people intuitively comprehend. You simply feel the rhythm. As you follow the beat, you unconsciously synchronize your feelings and thoughts to harmonize with the space. You may even find yourself coordinating your movements with others who occupy the space.

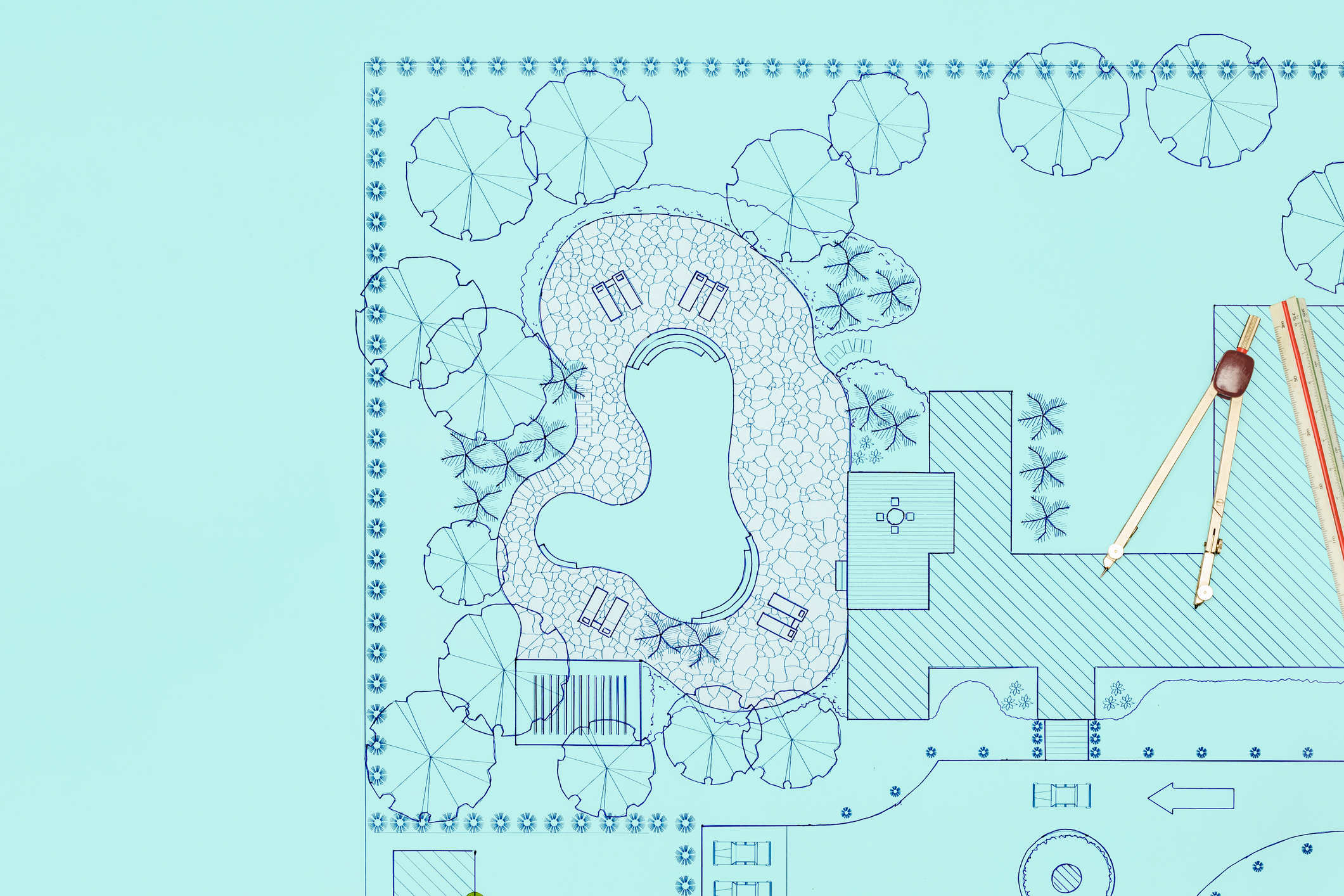

Natural stone and falling water: In contrast to the formal tone and straight lines of classic modernism, this WaterSpace sets an informal, natural tone with circles and curvilinear forms found in nature.

How Landscape and Architectural Rhythm Set the Tempo in Space

Rhythm is repetition. Like good dance music, rhythmic landscape architecture needs a repetitive, consistent beat that sets the tempo. You achieve consistency in the way you place elements and how they relate to one another. To keep the beat, you repeat the relationship you’ve established using the same elements. You can also employ different elements that relate in the same manner.

Note how the entire composition in the above design is held together through the colors and texture of natural stone. The smooth patio tile and coping at the pool’s edge repeat the colors of the rough textured stone. The fire pit at far right repeats the circular shaped spa area. The natural shapes of the large boulders—and the complete assemblage of of stones that create the waterfall—all repeat the pool’s informal curves.

Remember that you’re designing in three dimensions. The rhythms you create need to repeat up and down, left and right, near and far. You also need to account for how your composition’s look and feel changes in tone and character as you move through it.

Rhythm, Movement and the Music of Space

Some say rhythm is movement. But it’s a special kind of movement: movement synchronized by the space you’re occupying in a particular moment, by the path you’re following, and in coordination with those who have joined the journey. It’s the music of space. A silent rhythm that sets a spacial tone.

Rhythm in stone and water: Boulders rise from the ground to lift a waterfall high above the pool. Note how the design creates a rhythmic wave in stone, rising and falling in harmony with the falling water.

A hidden path: To the left of the falls facing the pool a hidden path takes you to a second waterfall.

To a hidden grotto: Your path takes you through the falling water and inside to a grotto, hidden behind two walls of falling water—except when the falls are turned off for our photographer.

As we described in our discussion of the Blue Mind, there is something about water that draws us to it. And when it’s moving water—a gentle trickle of a small fountain, a rushing stream, an ocean tide, or a powerful waterfall—our attention turns to feelings ranging from peace to awe to joy. That’s the goal of the WaterSpaces we build: for you to simply enjoy.

How Emphasis Sets the Scene for a Large Country WaterSpace

Emphasis: Setting the Stage for Outdoor Entertaining

You feel the good mood approaching as you enter the covered porch at the rear of this country home. Whether you’ve arrived for a daytime pool party or an evening dinner, you’ll likely be greeted by enticing aromas rising from the food prep area—set below ground level so as not to obstruct your view. This is the view that sets the scene, that assures you this is going to be a delicious experience.

An invitation to enjoy: your first view sets the scene for an entertaining experience

How Emphasis Focuses Attention

You may recall this scene from a previous article, “The Art of Emphasis: How Focus Adds Appeal to Your Outdoor Living Space.” Center stage you see a spa rising from the far end of the pool. Note how the spa is emphasized by its black tile set against a light, creamy wall. Like buttery French cream sitting atop a mug of dark black iced coffee, this is how contrast makes things livelier in your outdoor living design. Contrast is just one of the tools of emphasis employed in this design.

The power of emphasis also directs your eye by framing the view with the white roof you’re standing under, two white pillars on either side, and a black marble countertop completing the frame. Emphasis is at work through the repetition of a shape—the spa, the creamy wall, and the frame all repeat the same rectangular shape. Color is repeated in the black spa and marble counters. Repetition is the key element here in creating rhythm. As in music, rhythm in design keeps all the pieces playing together in an orderly manner. We will be discussing rhythm more in the next installment of our series on the six principles of design.

Rhythm suggests movement. One of the most powerful forms of movement in water design is reflection. In the above picture, notice how the pool reflects the shapes of the spa and wall behind it. Note how the pattern of light reflecting off the pool is repeated in shiny black marble counters and how reflection adds a touch of blue pool color to the white roof and pillars.

This is a scene where your mind says, “go explore.”

The Setting

At this point you may find yourself wanting to get a closer look, but first, let’s go overhead to view the major elements of this design.

A stage set for entertaining: 1: Covered porch 2: Infinity Edge Spa 3: Lawn and patio 4: Outdoor living room with large TV, bathroom, shower, and storage 5: Food prep area and swim up bar 6. Swimming pool with sun shelfs on two sides

Designing Space for Entertaining

The homeowners wanted a pool design that enhances their large outdoor space, which they use frequently for entertaining. They had initially thought of putting a large pool horizontal to the home, but this would have created a barrier to accessing the rest of the yard.

By turning the pool perpendicular to the yard, they gained better flow and accessibility. The spa, originally thought to be placed near the entrance to the home, could then be placed at the far end of the pool, creating a dramatic focal point, as we saw above in the first photo (above).

When entertaining larger groups, tables are placed on the patio and in tents erected on the lawn. For small, informal occasions, guests can take a seat at a bar in the kitchen area or on swim up bar stools (below).

Food prep area: Includes full kitchen facilities and grill for the chef, plus a swim up bar with stools, and a table area for those who prefer to stay dry

A Space for Reflections

The Spa Up Close: Water from the infinity edge spa spills into the adjoining pool

At the opposite end of the home’s WaterSpace, a black tiled infinity edge spa provides this mirror-like surface (above) that reflects trees and sky. Set off from the entertainment area, the spa also provides a spot for peaceful reflection and relaxation.

Harmony in Water, Space and Built Places

You may recognize the design style: formal and yet modern and contemporary, in concert with the home’s architecture. Even if you didn’t think consciously in those design terms, your mind would recognize and feel comfortable in this balanced space. In “Creating Harmony Through Architecture, Water and Space,” we explored ancient ideas about using water and outdoor space to create harmonious spaces in homes. It’s worth repeating a quote from Winston Churchill that appeared in that article: “We shape our buildings, and thereafter they shape us.” The same can be said of the space we create that brings outdoor living into our homes.

In her book, “The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain,” science writer Annie Murphy Paul devotes a chapter to “Thinking with Built Spaces” and another to “Thinking with Natural Spaces.” She discusses the emerging scientific evidence—along with millennia of human experience—that demonstrate how humans need harmonious settings, indoors and outdoors. Human joy and creativity thrive in environments that help set our minds free.

Paul cites Christopher Alexander, an architect and emeritus professor at U.C. Berkeley. He is author of “A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction” (1977) and wrote, “a person is so far formed by his surroundings, that his state of harmony depends entirely on his harmony with his surroundings.”

When we entertain the idea of creating our own WaterSpace, we have the possibility of bringing our outdoor space—the natural space—and our indoor space—the built space—into harmony. It turns out that when you build a more humanly enjoyable space, you’ve created a place where people think more creatively and interact more productively with other people.

The Art of Emphasis: How Focus Adds Appeal to Your Outdoor Living Space

Emphasis: It’s like creating a stage for the stars of your WaterSpace Design. If you’ve recently sold or read about selling a house, you’re probably familiar with the growing use of professional staging to lift a property’s value. The secret of staging rests in part on the art of Emphasis, the third of the six principles of design in our series.

When you set the scene by spotlighting a star in your design, you add luster to the entire environment. It’s a matter of focused appeal. Finding your emphasis may require adding something new, but just as often your design team can help you discover, develop and highlight a star attraction that could have been overlooked.

Focus and the Art of Emphasis

The art in Emphasis is not just calling attention to a star feature but rewarding the viewer’s focused attention. You want to create a layered experience akin to viewing a work of art. There’s the striking view from the distance and the greater detail to be seen up close. The more viewers move in closer to focus on the art, the more rewarded they feel.

In a previous article on the Design Principle of Contrast we looked at how contrast adds interest in water oriented outdoor living spaces. You’ll notice how both Contrast and Emphasis set out to make a design more interesting. Both are quite good at their jobs. But where contrast draws momentary attention, emphasis captures and holds attention.

Indeed, Contrast may be noticed only unconsciously. Even with High Contrast, the viewer’s attention is more diffuse than with Emphasis. You may notice the contrasting elements of a design—the nicely placed accent piece, the pleasing interplay of light and dark, of colors and textures and shapes—but none of it is intended to hold your eye. Emphasis, on the other hand, is about capturing, holding, and rewarding attention.

When considering the elements for emphasis, be sure to consider both space and movement through the larger space. For your “performing art” to receive proper emphasis, it needs artful placement in its space. But what you’ll see in your space—what role each element plays—changes with movement.

Different Stars for Different Scenes

Like in the movies, there can be more than one player in a starring role. As a play or a movie moves forward, settings and scenes change, and the role each actor plays grows, diminishes or even disappears. As you move though a well planned and executed outdoor design, you’ll discover it has more than one setting—a different point of emphasis, a different star to entertain your attention from each new perspective.

Coming up next: Stars, Stage and Mood

In choosing your stars and creating your space, look beyond technique and think about the mood you want to create. All three—star, stage (space), and mood—need to work together.

In the next edition we’ll look at the elements of emphasis, the art of placement, and the moods they engender. Water features, artistic works, architectural features, the natural setting, the things you plant, and the colors and materials you employ all play important supporting roles—some may even become stars. It’s all a matter of Emphasis.

Whisper and Shout: Use Contrast to Add Interest to Your WaterSpace Design

Things get livelier when you add contrast to your outdoor living design

Wherever you add an unexpected change in color, or shape, size, or texture, you’ve got contrast. In this article on the second principle of architectural and landscape design, we’ll look at how contrast helps us achieve that delicate dance between the comforts of a well-ordered space and the need for something that catches our interest.

In the first principle of design we explored how humans can’t tolerate a lack of balance (story here). But it turns out humans find too much balance is…just…plain…boring. We use the principle of contrast to mix things up—to keep it interesting.

Change Colors for Contrast

Of all the ways we can create contrast, color is the easiest to employ and the most readily noticed by a casual observer. Color contrast can be stark—like black and white or bright red against equally bright green—or subtle, as in shades of gray or white tints.

Color contrast is achieved through the choice of hue—think of all the colors in the rainbow with their infinite variations and combinations. Or you can change the value—a lighter tint or darker shade. The greater the difference in value, the greater contrast. (Learn more about designing with color here)

Change Shape and Size for Contrast

Shape and its partner size play a large role in outdoor living spaces, and they do it in three dimensions. When you think about shape and size, you also have to take scale and proportion into account. Scale concerns how large or small things appear in a landscape. How does a landscape feature or a built element appear in relation to other features and elements? Proportion concerns how these shapes relate to one another. Proportion can be pleasing, or interesting, but it goes wrong in a hurry when size and shape go too far out of balance. (Learn more about shape here)

Add Texture for Contrast

In many ways, texture is the essence of contrast. Unless you’re a designer, you probably think of texture as how a rough or smooth surface feels. If it’s called “textured” it’s definitely not smooth. In design, texture adds visual interest. But it has to do so in harmony with the overall design. In “The Tao of Texture” we explore the benefits of adding texture and harmony to your WaterSpace—really any living space you occupy. You can get the whole story here.

Look to Water and Nature for Contrast in Motion

Motion and contrast. It’s how water and nature keep capturing our interest. They look familiar, comforting, and yet every new moment offers the possibility of new contrasts, new delight, and surprise. Sometimes new contrasts arrive in slow motion, as when plants and trees grow, or bloom, or change colors with the seasons. Other contrasts arrive like clockwork with the movement of the sun, or more suddenly with the passage of clouds. Water features, such as falls and fountains, bring continuous changes in colors and sounds. And then there’s reflection, water’s mysterious change artist. You can read more here, in “Discover the Hidden Power of Reflection.”

Add an Accent or an Exclamation!

Low and high contrast are the accent marks and exclamation points of design. Designers often talk of accent pieces that add contrast ranging from subtle to bold. Even bold accents don’t have to overwhelm the space. Think of the difference between an accent mark—emphasis on a particular part of a word—and an exclamation point that turns a whole word or sentence into a shout.

Accents in landscape architecture offer softer contrast—the smaller, more subtle design element that adds interest without shouting or calling too much attention to itself. It’s a milder voice, making a quiet but firm statement in favor of a little more contrast.

High contrast, like the exclamation point, carries more weight than the accent. The higher the contrast, the louder the voice speaking out against conformity. Just be careful. Bold contrast needs to be handled with care and skill. Get contrast wrong, and one contrasting element cancels out another—just like those noise canceling headphones. Get contrast really wrong, and the whole design concept gets overwhelmed in noise.

For more about accent and contrast, go here for a brief discussion on britanica.com. While there, I’d recommend reading the entire article, “Garden and landscape design” for a good overview of design and landscape architecture.

Coming up next

In the next edition we’ll be looking at emphasis. You can find a summary of all six principles of design here.

Keep Your Balance: the First Principle of Good WaterSpace Design

Use balance to pull together all the elements in your outdoor living space

Just as we can’t stand erect without balance, humans can’t stand an environment lacking a sense of balance. Like our physical balance, we don’t consciously notice balance in built spaces. Until it’s missing. Then it may be too late.

Balance in 3-Dimensions

Artists and photographers work on a flat, two-dimensional plane and have an array of design techniques to achieve balance. However, architects, builders, and landscape architects work in three dimensions.

The third dimension provides fewer options for achieving balance and opens troublesome opportunities for overlooking imbalance in some area of the design. A design can look fine on paper, but when built and viewed from some angle, something may feel unbalanced.

Our best choices in three dimensional designs come down to symmetrical or asymmetrical balance. In any design, both symmetrical or asymmetrical balance rest on visual weight. Balance is largely achieved by shape, with some help along the way by texture and color.

We call it visual weight because physically heavy features (say, stone) on one side can look balanced to the eye by placing lighter objects on the other side—lattice or windows, for example—that visually match the stone’s mass. You can do the same with masses of plants, trees, open spaces or water features.

Symmetrical Balance and Pleasing Style

Symmetrical Balance and Pleasing Style

Balanced designs are pleasing designs. Symmetry gives your space an orderly, structured, carefully planned feel. It starts with straight lines and neat circles, all lined up along a central axis. Each side of the center line is the mirror image of its counterpart.

Symmetrical, balanced designs appeal to our senses. They feel comfortable, predictable, safe, when done with restraint and on a human scale. You can see this in classic public buildings in Philadelphia. Think red brick and Independence Hall, or its smaller and less famous neighbor, Carpenter’s Hall.

On a grander scale, balanced, symmetrical design declares order, grandeur, and authority. Think marble and the larger, more imposing buildings in Washington, D.C., or just about any capital city. You can find the same large-scale symmetrical balance in India’s Taj Mahal, and many of the most picturesque museums, art galleries, university campuses, parks, and estates.

Asymmetrical Balance and Interesting Style

Asymmetrical Balance and Interesting Style

Asymmetrical balance brings out the artist, the interesting detail, a focal point, a place that holds your eye, that moves you forward. It can be fun, even daring.

It still supplies the balance we need to feel, but it brings out more opportunities for individual style to express itself.

You find asymmetrical balance in nature. Natural can feel more casual, calm and relaxing—like a quiet pond—or wilder, looser—like a rushing river or incoming tide.

You Can Blend Symmetrical and Asymmetrical

Skilled designers will blend symmetrical and asymmetrical balance, giving you the best of both. You can create a pool area that is modern, formal. There’s no mistaking its symmetrical balance. The straight lines and rectangular shapes with sleek, smooth surfaces feel cool, contemporary, sophisticated.

The adjoining garden can be made up of curved lines, irregular shapes. Its asymmetrical balance is in harmony with its neighboring pool area, and at the same time it provides a welcome contrast. You can feel the garden’s warmth in the designer’s rendering. You can imagine the visual interest and seasonal changes nature brings to the setting.

Sometimes it’s OK to Get a Little Off-Balance

There are times when a clever designer—and brave clients—may choose to get a bit off-balance in their design. Off-balance designs can become an interesting point of attention, or an unwelcome distraction. Even a little off-balance can look like a mistake (and probably is)—unless it’s done purposefully and with great skill.

I wouldn’t recommend no-balance designs. This creates visual chaos. Without clear purpose—and some visual relief—chaos is disturbing to the eye and unsettling to the body.

A Question of Style: Fashion Trend or Fad?

In my Introduction to our series on design principles, I touched on how the style you choose will point you toward the balance you’ll need.

We’re all influenced by trends in style. Inevitably, some disappoint and turn out to be fads. When styles in architecture are trends, they last for years, decades, centuries. When a new style is a fad—suddenly fashionable overnight—it can become unfashionable even faster.

The good news is that today’s big outdoor living trend is Modern—or Modern Contemporary. The trend started on the West Coast and has moved east. The Modern Contemporary style is a fresh take on 20th Century Modern. Modern style’s roots go way back, to Classic Greek architecture and the Greek Revival styles that arrived in America in the 19th Century.

When you think about style, take a wide view to start. You don’t want to limit your initial thinking to the one thing that appears fashionable now, or the one thing that’s been your default forever. Get to know various architectural and landscape styles, learn as much as you can about design elements and principles. Allow yourself the time to find the style that pleases you, that fits your needs and feels right for you.

Then get the best design help you can find. Whatever the style, good design is timeless.

Design Choices: Follow these 6 WaterSpace Design Principles

We all want to have design choices, to make our own choices. But have you ever been overwhelmed by too many choices? It happens a lot with the abundance of choices we have in America, and it seems to happen daily, now that we’re buying so much online.

Believe me, it’s going to happen frequently when you start creating your own outdoor living space. From imagining to planning, to building, there are hundreds—no, thousands—of small and large decisions to be made. And some of those seemingly inconsequential decisions may have very large consequences later on. That’s why every design decision has to be intentional, not accidental.

Of course you can avoid accidents if you’ve engaged a competent designer. But if you want to participate in the choices (and you should), you need to understand the reasons behind your designer’s recommendations. In this next series of articles on WaterSpace design, I’ll explain the six design principles that help you and your design team make the right choices.

Design Principles: Your First Choice

In this series, we’ll be referring back to the five elements of design that we covered previously: Space, Shape, Line, Color and Texture. The design principles we’ll be discussing provide the framework for how and why you chose to use these elements.

It may seem a little backwards that we started you off with the elements of design, and now we tell you to start your design based on principles that I’m just now introducing. But as I explained in the first article, the best pool and WaterSpace designs start with the space where you place the pool, and of course designers want to uncover early on your personal preferences for elements such as shape and color. When you’re ready to start thinking about the bigger picture that pulls it all together, that’s the time to think about which design principles you want to apply.

So as to avoid keeping you in further suspense, I’ll provide a brief overview of all six design principles: balance, contrast, emphasis, rhythm, movement, and unity. Let’s take them one at a time.

Balance

You have two choices when it comes to balance: symmetrical or asymmetrical.

◦ Symmetrical: Symmetry brings formality and grander to your design. It’s classical Greek temples and Roman villas, the French formality of Versailles, Tudor, and Neoclassical.

◦ Asymmetrical: This is nature’s balance. It’s an informal, natural look that goes well with rustic materials.

Contrast

You can hit a High C or a Low C with contrast.

◦ High Contrast: Go bold with high contrast. Stand out. Grab attention. Pull the eye toward one thing, or group of things, that say “look at me.” Get excited. Or sophisticated. Be noticed.

◦ Low Contrast: No standouts here. Plays nice with others. Fits in and fits together with other elements. Relax.

Get calm. Meditate. This is the level of contrast you want when you’re going for Unity, our sixth and final design principle.

Emphasis

Emphasis is artful. Like High Contrast, it lets you set a piece of your design apart from the rest.

◦ Focus on something or some area you want noticed. Everything else is background.

◦ Create a space to put a special sculpture or a fine piece of art on display.

Rhythm

Just as the ear enjoys the rhythms of music, your eye is attracted to the rhythm of objects. Rhythm eliminates that feeling of randomness and cleans up a cluttered look. It’s important to add rhythm to your design when you want Unity. Break this principle of Rhythm only when you intend to go for Emphasis or

High Contrast.

◦ Repetition: Use the same things repeatedly throughout the design

◦ Consistency: Create and maintain consistent patterns in your design

Movement

This one is fun. It’s design that moves eyes and feet to explore a space.

◦ Visual Movement: Movement captures the eyes, takes them across the scene, and brings them to rest on a carefully chosen focal point.

◦ Physical Movement: This is movement designed to inspire curios feet, an urge to see what’s around the corner. It’s about discovery and surprise.

Unity

Unity is the only design principle that most spaces must achieve. You don’t break this rule unless you’ve purposely chosen to pursue High Contrast or put Emphasis on a special element.

Up Next

In following articles we’ll go into greater detail on these six essential design principles. Next up, we’ll look at achieving balance in your designed space.

Philadelphia’s Fairmount Water Works – America’s Most Famous WaterSpace

‘A Place Wondrous to Behold’: How Philadelphia’s Place for Pumping ‘Utility Water’ Became America’s Most Famous WaterSpace

In the mid-19th century, Philadelphia’s Fairmount Water Works was a world famous tourist attraction. It was the second most visited attraction in America (first place went to that most famous “water feature,” Niagara Falls). Upon his visit in 1842, Charles Dickens called it “a place wondrous to behold.”

The Water Works remains a wonder to this day for those who visit this beautifully restored space in Philadelphia. In this installment of our “Just Add Water” series, we’ll look at how natural beauty, a river and its pristine water, technology, architecture and landscape design created a place where “beautiful water” and “utility water” became one.

The Wondrous Effect

I seldom (if ever) hear the word “wondrous” used when clients tell me what they want to achieve with their home’s WaterSpace; yet a feeling of wonder is precisely the effect we’re all seeking. It’s that combination of joy and awe in a waterscape’s natural and planned beauty. Fairmount is one of those wondrously designed places—places that allow us to live or play or simply be in the presence of a wondrous WaterSpace.

In the background, behind those visual and sensual pleasures, the Water Works housed wondrous technologies. It demonstrates how the built WaterSpaces we admire—the experiences we seek out in public spaces and private places—have achieved a marriage of design on a human scale and technologies that make the space habitable and sustainable.

Today’s Fairmount Water Works can teach us a lot about designing our own wondrous WaterSpaces. Let’s break it down into four essential pieces:

- Health: The driving purpose we can never forget

- Technology: The knowledge and tools that are worthy of our wonder, even in today’s jaded technosphere

- Design: Functional design with an eye for beauty, human scale and interaction

- Stewardship: The connections and responsibilities beyond our backyards

-

Health: the Wonder of Safe Water

By the time the United States wrote its Constitution in Philadelphia, water had become a major health hazard for those living in the city. Benjamin Franklin observed, “In Philadelphia everyone has a cistern and a well, and the two are becoming indistinguishable.”

In its history of the Fairmount Water Works, the Delaware River Basin Commission (DRBC) tells the story:

“There was filth in the streets and not enough water to wash it away. And what little water there was came from the city’s wells, by then fouled with waste from nearby cisterns (drains) and cesspools.” (From DRBC’s “Fairmount Water Works: A Place ‘Wondrous to Behold’,” click here for full article)

In 1790, Franklin’s bequest of 100,000 pounds provided the initial capital for the city to develop an abundant water supply to “insure the health, comfort and preservation of the citizens.” By 1815, Philadelphia was the first American city providing safe drinking water and enough to clean the streets, too.

Today we turn a tap and fill our pools and spas with healthy, clean water. To keep it healthy, however, you need to be diligent about testing your water (see story here) and keep the right balance (learn more here).

Technology: the Wonder of Effortless Access to Safe Water

In the 19th century, water as a utility was a wonder. “It is impossible to examine these works without paying homage to the science and skill displayed in their design and execution,” Thomas Ewbank wrote in 1840. Ewbank had first hand knowledge of the subject. He started as a plumber at the age of 13 in England, became a manufacturer of lead, tin and copper tubing in New York, and the United States Commissioner of Patents in 1849.

Great machines (first wood burning steam engines and later water driven turbines) and engineering talent made it possible to pump clean water from the Schuylkill River up to a reservoir built on top of the “Faire Mount” that stood above Philadelphia. From there, gravity did the work to deliver clean water to homes, breweries and fire hydrants, which would have pleased Franklin who liked his beer and started the city’s fire department.

The news that Philadelphia could provide safe drinking water on such a scale brought worldwide attention to the new Fairmount Water Works. Today we call it “tap water” and take it for granted. The Fairmount story reminds me that, when we create a WaterSpace, we first need ample access to clean water to fill the pool and spa—and be thankful we don’t have to haul the water in.

You can still experience the engineering wonders that brought tourists to the Fairmount Water Works. The Interpretive Center is closed at the moment as a result of COVID-19, but it expects to reopen soon. The grounds are already open to visitors, and there’s an app available for a guided tour (click here for information).

Design: Creating a Wondrous Space

As it expanded, the Water Works buildings were surrounded by formal gardens, statues and fountains, giving visitors a wondrous mix of the latest technology, natural beauty, architectural interest, and landscaped paths that led through the outdoor spaces and up the steep hill to the reservoir.

According to the DRBC’s history, “Painters and photographers captured the grace. Pictures of the stately buildings and the river, dotted with boats, appeared in 19th century ads for ice skates, on firemen’s hats, sheet music, pottery, porcelain and gilded vases.”

The Water Works was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1976. The original nomination document quotes Frances Trollope from her “Domestic Manners of the Americans.” Trollope called it, “one of the very prettiest spots the eye can look upon.” (A pdf of the document can be seen here and a story here).

Fittingly, after the Water Works was decommissioned in the early 20th century, another iconic Philadelphia landmark was added to the scene. Built in 1924, the Philadelphia Museum of Art now stands at the top of the mount where the Water Works reservoir was located. In a single view, you can to see art’s presence in classic industrial design, the surrounding landscape, and the architectural gem housing one of the world’s great art collections.

In my series on Water and Space, I led off with “Why the Best Pool Designs Start with the Space” (here). A visit to these public spaces lets you experience those same principles.

Stewardship: Keeping the Wonder and the Water Safe

When water is safe for drinking, it’s safe to swim in or play in the water as well. But as Philadelphia and many other communities have learned, you can’t safely go in or drink from a polluted river. Anticipating the problem of upstream pollution, Philadelphia used its profits from the Water Works to buy the land that’s now Fairmount Park. But it wasn’t enough:

“The buffer land that would form the biggest city park in the world wasn’t big enough to protect the Water Works. The pollution flowed downstream from Schuylkill Valley coal mines and dairy farms and from upriver towns like Pottsville, Reading, Pottstown, and Conshohocken.” (DRBC history)

It would take years to clean up the river. In the meantime Philadelphia turned to a newer technology, adding five pumping stations along the river with sand filtration beds to purify the water. The Fairmount facility lacked room for filtration beds. After 94 years of operation, it was closed in 1909.

This part of the story is especially important. We all depend on easy access to safe water for our homes—the “utility water” as Charles Fishman calls it. (See “Take a Dive Into the Science of Water” here). As Fishman noted, we tend to divide “utility water” from “beautiful water,” giving little or no thought to the utility part. Yet, as the Fairmount Works demonstrates, nature’s water, utility water and beautiful water are all connected. When we don’t care for water at the source, in the long run we lose both utility and beauty.

Take a Dive Into the Science of Water

Let’s look at the science of water. This article is the second in the “Just Add Water” series inspired by Wallace J. Nichols, author of “Blue Mind” and founder of the Blue Mind movement

We all know water is H2O—two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen—but very few appreciate just how strange and magical the chemical is. Sometimes it’s even a struggle for science to explain water’s surprising properties. Let’s take a dive into some of those mysteries and what it means for those whose “Blue Minds” are driven to create a WaterSpace at home.

In his chapter, “The Senses, the Body, and ‘Big Blue,’” Blue Mind author Wallace J. Nichols quotes Charles Fishman’s observation about how water can lighten your mood. “A bright mountain stream makes you smile,” Fishman says. It “makes you feel better.”

The quote comes from the book, “The Big Thirst,” by Fishman. It’s the most accessible guide I’ve found to understanding water’s unusual chemical properties and appreciating its essential role in making life both possible and beautiful. Fishman’s book sets out to correct what he sees as widespread water ignorance. He takes the reader back billions of years into the earth’s history, and forward on a worldwide tour of today’s water uses and misuses.

The Science of Water Chemistry is Complicated and Weird

As I wrote here, when you bring a new pool or hot tub into your home, you have to become aware of the basic water chemistry that keeps it safe for people and prevents damage to your pool or spa. Even if you don’t have one at home, the article provides tips for judging whether it’s safe to get into that pool or spa at a resort, club or public facility.

Fishman’s book takes you even deeper into the weird science of water chemistry. “Water is a complicated, unusual, almost enchanted substance,” he writes; “not in the emotional or cultural sense, but literally, physically, starting right at the molecular level.”

Water inherits its odd character at this molecular level. It starts with hydrogen bonding creating an unusual level of “stickiness.” The stickiness enables water’s unique properties. There isn’t room here to include all the scientific observations Fishman provides in his book, but let me share a few examples:

• 32-212 Degrees of Life Support: “Water is a liquid through an incredibly wide range of temperature, Fishman says, “…and it is liquid over a range of temperatures hospitable to life.”

• Living things live thanks to liquid water: “Much of the chemistry and biology,” Fishman says, “…requires not just water, but liquid water.”

• Water regulates temperatures for life and earth: Fishman says, “stickiness allows water to absorb and hold heat,” making it an insulator that living things use to regulate their temperature. Water helps regulate the earth’s climate by allowing ocean temperatures to “vary just one-third as much as land temperatures.”

• Ice floats and life survives: Solid materials are supposed to be heavier than their liquid form. But water forms ice, “a crystal lattice that is 9 percent less dense than the same amount of liquid water.” Fishman explains how sticky hydrogen bonding lets ice float, another weird water property that makes the earth habitable.

• Water is a great solvent: In an article on keeping water balanced in your pool and spa, I noted how water wants to combine with just about anything it touches. Fishman tells us why: “almost anything will dissolve in water, in part because of its polar molecules.” He says the chemistry of our bodies—such as converting food to energy—depends on water’s super solvent ability. He adds, “Solvent qualities also mean water is easy to pollute, and that water is a great harbor of all kinds of things that make people sick, from germs to heavy metals.” Keeping water healthy helps keep living things healthy.

Scientists “go mystical” about water

This amazing chemistry that keeps water liquid, that lowers its density when it becomes ice, that makes water’s life-supporting properties possible, “are the kinds of qualities that cause even scientists who study water to go a little mystical on you,” Fishman says. It all “makes perfect molecular sense—if you’re a chemist or a physicist…. And yet nothing else in the regular world does that, and it is precisely that quality of water that enables life to go on living.”

What water is

Fishman worries that “we know nothing of the life of water—nothing of the life of the water inside us, around us, or beyond us. But it’s a great story—captivating and urgent, surprising and funny and haunting.” His chapter on “The Secret Life of Water”—from which this article provides a small sample—fills the reader to the brim with scientific knowledge of water.

But of course the chemistry is just a small part of the big water story. What does that magic chemistry mean for us now and for our future, and why is it important to understand water more fully? Before ending his chemistry lesson and moving on to a global tour of how we use water, Fishman offers these thoughts on what water is:

- “Water is transparent, and also reflects light.

- Water is soft and soothing, and also hard as concrete.

- Water is comforting, and also threatening; gentle, and fierce.

- Water is the source of life, and also often a source of death.

- Water is all-important, indispensable, but almost always free, or essentially free.

- Water is the most basic necessity to human life, and also a symbol of luxury and indulgence.

- Water is sexy and alluring, and also often appalling and repugnant.

- Water is as natural and wild as anything in the world—from white-water rapids and waterfalls to the power of hurricanes—and yet water is thoroughly domesticated in everyday life.

- Water is a team player—a partner in a cosmic gallery of natural events—and yet water has an independence of both body and spirit. It participates in all kinds of processes but emerges again as simply water.”

Up Next: The beauty of water and utility water

“We often keep the two kinds of water separate in our brains and in our day-to-day stewardship,” Fishman observes, “utility water and beautiful water.” There was a time when modern utility water was seen as a marvel of enlightened progress. In the next installment of “Just Add Water,” we’ll look at the leading role Philadelphia played in making safe drinking water a modern utility and how a bequest from Philadelphia’s most remarkable citizen made it possible.

LED the way: Light your Nighttime WaterSpace with New Outdoor LEDs

A host of new LED lights are making outdoor lighting more accessible, affordable, and a lot safer than those 120-volt wires running in conduit under your garden or patio. Now is the best time ever to upgrade the lighting in your outdoor living space.

Before you click “buy” on that online order, however, take time to develop a lighting plan. While LEDs make outdoor lighting easier and friendlier on your budget, you’ll still need to tackle a few technical details, wade through all the LED options, and design a plan that achieves the lighting effects that you want.

Artful Outdoor LED Lighting

In the article, “Color Choices in Pool Design” (see story here) we looked at how light changes colors in an outdoor environment. White light isn’t all the same, and its different tones (temperatures) change the colors you perceive. Like color, light has an enormous impact on our mood. Night lighting can be dramatic, soothing, exciting, or annoying. Creating a lighting design that adds pleasure and value to your home is an art. You either learn the art of lighting or get professional help from a designer.

Whether you decide to do it yourself or get help, there are some basic design principles you should be aware of:

- Think 3-D: In planning light placement think like a designer or architect and consider all three dimensions. Lights can be placed high, low or someplace in the middle, depending on use and the effect you envision. Visualizing lighting in three dimensional space—and getting it down on paper—can be a tall order. For more on 3-D design, click here to see “What Shape Means when Planning a WaterSpace.”

- Think Direction: Your lights can point up or down. The beam can be narrow, broad or defused, adding a subtle, directionless glow that spreads across the space.

- Think Intensity: Modern LEDs are dimmable, which gives you even more latitude in designing for effect. You can even automate your levels to adjust to the progression of available natural light from evening to night.

- Think Carefully about Blinking Lights: Just about any LED system that lets you dim the light also lets you make them blink with the push of a button, often offering a variety of blinking patterns and even changing colors. Used with care, you can avoid the Broadway at nighttime or Vegas strip vibe, but you should also understand that the human eye is finely tuned to focus on movement, even in your peripheral vision. Flashing lights easily become distracting, bordering on irritating.

-

Outdoor LED Power Options

You have three ways to power your LEDs but only two can give you bright enough and sufficiently reliable light you can depend on.

- Wired LED Lights: All you need is a transformer to step down your household current from 120 volts to 12 (get an electrician or contractor to do this part). You don’t need to dig up the ground to bury conduit for the wire. You can safely lay the wires on the surface of a garden and cover them with a little mulch. And if you should accidentally cut a wire, no one is going to get choked, much less electrocuted.

- Battery Powered LEDs: LED lights last a long time on battery power. They’re portable so you can put the light where you need it right now. And there are creative and beautiful battery powered lights available today.

- Solar Powered Lights: The solar LEDs you can buy at the big box stores aren’t a viable option for extended outdoor use. Even if you were lucky enough to get a full charge during the day, the light is too dim and the stored energy too little to last into the night.

-

Well designed, modern LED lighting can add texture and visual interest to your nighttime living space. With the push of a button, your lights can bring excitement and drama, or calm and serenity to the same place. An October, 2020, analysis by realtor.com found that homes with landscaped outdoor living spaces helped sell houses faster and at higher prices. Artful lighting of your WaterSpace is among the most cost effective ways to extend your outdoor enjoyment and add more resale value to your home.

Just Add Water: The Science of Water and Wellbeing

Let’s look at the Science of Water and Wellbeing. This is the first in a series of articles inspired by Wallace J. Nichols, a PhD who has turned his passion for water into his life’s work. He is the author of “Blue Mind: The Surprising Science That Shows How Being Near, In, On, or Under Water Can Make You healthier, More Contented and Better at What You Do.”

The “Blue Mind” book, and his research, Blue Mind Conferences, public appearances, and blog have had a profound influence on me and on millions of people around the world. Nichols is one of those unique individuals who doesn’t just research, or teach, or preach about the deep connections between water and humanity. He lives it and writes from firsthand experience.

A ‘lab rat’ jumps in the water

“I’m a human lab rat,” Nichols writes in the opening paragraph of his book, “here to measure my brain’s response to the ocean.” He jumps off a pier on North Carolina’s Outer Banks, wearing a skintight cap bristling stainless steel connectors with long cables connected to a mobile electroencephalogram (EEG) unit.

The device was developed by Sands Research, the same company whose advertising impact studies produce the Annual Super Bowl Ad Neuro Ranking report. The 68 electrodes plugged into his head track every neurological response to his plunge into the ocean.

This dive is a success but it’s just one of a multitude of research projects reported by Nichols that tell us more about human responses to water. His interest extends to water in all its forms, uses and places, from bathtubs, to pools and ponds, streams, rivers, lakes, bays, and oceans.

Blue minds assembled

In 2011, he assembled the first Blue Mind conference in San Francisco. It was to become an annual event where he brought together, “neuroscientists, cognitive psychologists, marine biologists, artists, conservationists, doctors, economists, athletes, urban planners, real estate agents, and chefs.”

Like the book, Blue Mind conferences would “explore the ways our brains, bodies, and psyches are enhanced by water.” It’s all part of his quest to understand, “how humanity interacts with our watery planet.” Thanks to Nichols and the diverse array of researchers, philosophers, and water workers he introduces us to, we can see more clearly how deeply human wellbeing is tied to water.

We’re attracted to water because we are water

How could we not be drawn to water? Nichols tells us we came from water, and our bodies are water containers. The human body is almost the same density as water. It’s why we can float.

◦ We are 78% water at birth, 60% as we grow older

◦ The brain remains at a steady 80% water throughout our lives

◦ The minerals and salts in our cells are nearly the same composition as seawater

Water is everywhere and we want to be near it

As Nichols points out, 70% of the earth is covered by water, and 80% of the world’s population lives within 60 miles of an ocean, lake or moving water. Yet, many want to get closer.

We have a relationship to water that reaches beyond the biological need to satisfy our daily thirst. Seeing water, hearing water, smelling water, being by water, on water, in water. If we can’t live by a body of water, many of us will travel long distances to experience it, even for a short time. In urban areas we will seek out water settings, or create our own WaterSpaces—a pool, fountain, pond, or some water feature in our homes. We prefer to work, shop and dine in places near water and will pay a premium for a home or a room with a water view.

These may seem less urgent needs, but as Nichols writes, they are often tied to biological drives, or mental and health needs that want to be filled—perhaps can only be filled—through our connection to water. This water connectedness is part of what the philosopher and psychologist William James called mystical consciousness, “an awareness entirely different from our typical waking state.” James wrote:

“We are like islands in the sea, separate on the surface but connected in the deep.”

In future “Just Add Water” articles, we’ll explore how many of our environmental water needs can be filled right at home. And we’ll also look at how you can join the growing trend of people helping others to understand The Science of Water and Wellbeing and to experience a deeper relationship with our blue planet.