Design for Movement in Your Outdoor Living Space

Eyes move, minds move, and people enter the flow of space.

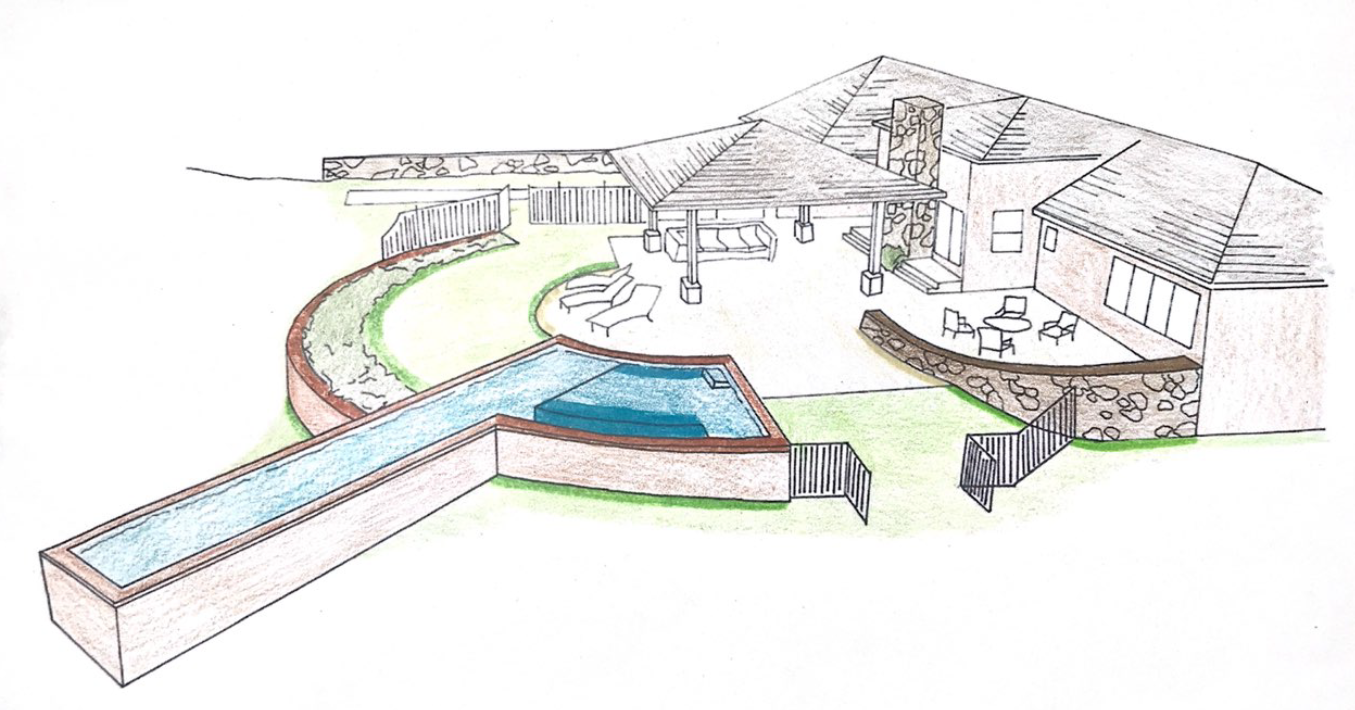

Architectural lines move minds and bodies: The rendering above illustrates how straight lines, curves and angles create a sense of movement in our minds. The dramatic lines of the lap pool show how lines create a shape that invites our bodies to join in the movement

Pools, buildings, and landscapes seem so firmly anchored to the earth that Movement—the fifth of our Six Principles of landscape and architectural design—can be hard to comprehend. Even when you don’t consciously see architectural movement, however, you’ll sense its presence, and you’ll likely find yourself getting bored if a design lacks movement.

In “The expression of movement in architecture,” (The Journal of Architecture Volume 16 Number 4, published 2011), Adam Hardy describes how built places are filled with allusions to movement: “sun and shade play across the walls,” he says, and “the breeze wafts through” a space. Sometimes, he adds, things actually move, as when “foundations settle.”

In most cases, Hardy says, “it’s not the architecture” that’s moving but the mind’s perception: “A staircase rises… a corridor snakes, a spire soars. Everybody knows, of course, that they all stay still: it is the eye and the mind that rise or run.”

People need movement

Make water move and people feel the movement. Add a lap lane (or lap line) to your pool, and people are more likely to swim. But even sitting still, people look for movement. When you think about and plan for movement in design, you’re paying attention to how people will feel, act and react in your space.

A single line helps us get physical, turning this informal curvilinear pool into a swimmer’s lap lane.

Movement In and Through Space

Move slow: Stones slow your pace and your gaze.

A lap lane is like a path in water. Designs with movement also create paths and patterns in our minds. Movement prompts people to look in a certain direction and perhaps move in a certain way. Some design features, like the lap lane, literally move us:

◦ Down a path leading to a pool, spa, garden, or other feature

◦ Along a line of trees, bushes or low plants that direct us through a space

◦ Through an arch, columns, or a doorway that opens onto a view we want to visit

Lines, Textures and Movement

Eyes follow Movement the way feet follow paths. Your eyes move along a line until you see an end point. Like walking along a path, your eyes move faster when the line is straight. Your gaze slows a bit when you encounter a slight angle or gentle curve and slows more for a long or sharp curve.

In landscapes, plants can direct eye movement and help define lines. Low and rounded plants prompt your eye follow a line. A taller tree or shrub placed along the line will cause your eyes to pause or stop.

Just as texture underfoot affects our speed along a path, the texture and colors of plants and building materials affect how quickly our eyes travel along a visual path. Smooth surfaces move eyes faster. The rougher the texture, the slower the pace for eyes and feet.

Movement engages all our senses

Step by step: Steppingstones direct you along a path. When crossing water as above, you may find yourself feeling your way along.

“So much of how we perceive the world is unconscious,” Nina Kraus writes in “Of Sound Mind: How Our Brain Constructs a Meaningful Sonic World.”

Krause explains how hearing developed out of the need to sense movement. “The ear arose,” she says, “from organs designed to perceive gravity and an organism’s place in space with the goal of achieving movement.”

As Krause points out, simply listening to speech “activates the motor cortex as well as our own speaking muscles. Just listening to rhythm patterns or piano melodies activates the brain’s motor system.”

The same could be said of the movement, rhythm and patterns created in our designed spaces.

We may not be aware of just how much our senses are engaged when see, hear or feel movement. But the effects of movement created by design are real. Designing for movement is an essential part of what people perceive and how they react in a built space.

As we described in our discussion of the Blue Mind, there is something about water that draws us to it. And when it’s moving water—a gentle trickle of a small fountain, a rushing stream, an ocean tide, or a powerful waterfall—our attention turns to feelings ranging from peace to awe to joy. That’s the goal of the WaterSpaces we build: for you to simply enjoy.